How many second-hand and vintage shops does your city have? And how many people are employed locally collecting, sorting, reselling, repairing, and upcycling garments? The textile reuse sector is growing, creating new economic opportunities for local circular businesses, entrepreneurs, and endless space to unleash creativity.

Reusing garments is a central part of making textiles circular. However, like with most other waste streams, circularity comes with a complication attached: it is virtually impossible to make the circular economy work without reducing the volume of new products going on sale.

There are already enough clothes in the world to dress the next six generations, so what is driving this unnecessary growth in the sector? In the EU, clothing prices decreased by 30% between 1996 and 2018 relative to inflation. This development was enabled by the increasing use of cheap, synthetic fibres from fossil resources and the relocation of production to jurisdictions with poor labour and environmental standards. The subsequent rise of fast-changing fashion trends resulted in so-called 'style consumption' rather than consumption to meet physical needs. The dominant business model in the fashion industry today relies on persuading consumers to continuously buy new fashion trends. Constant advertising and the widespread use of social media have perpetuated this trend. Studies show that in 63% of cases, clothes are disposed of due to poor fit and perceived value rather than the quality of the garment.

Increased clothing consumption has created a staggering waste challenge. The EU-27 generated an estimated total of 6.95 million tonnes of textile waste in 2020—around 16 kg per person. Of this, only 4.4 kg were collected separately for reuse and recycling, while the rest ended up in the mixed municipal waste stream. While as of 2025, the separate collection of textile waste is mandatory, the current capacity for collection, sorting, reuse, and recycling is insufficient, as shown below.

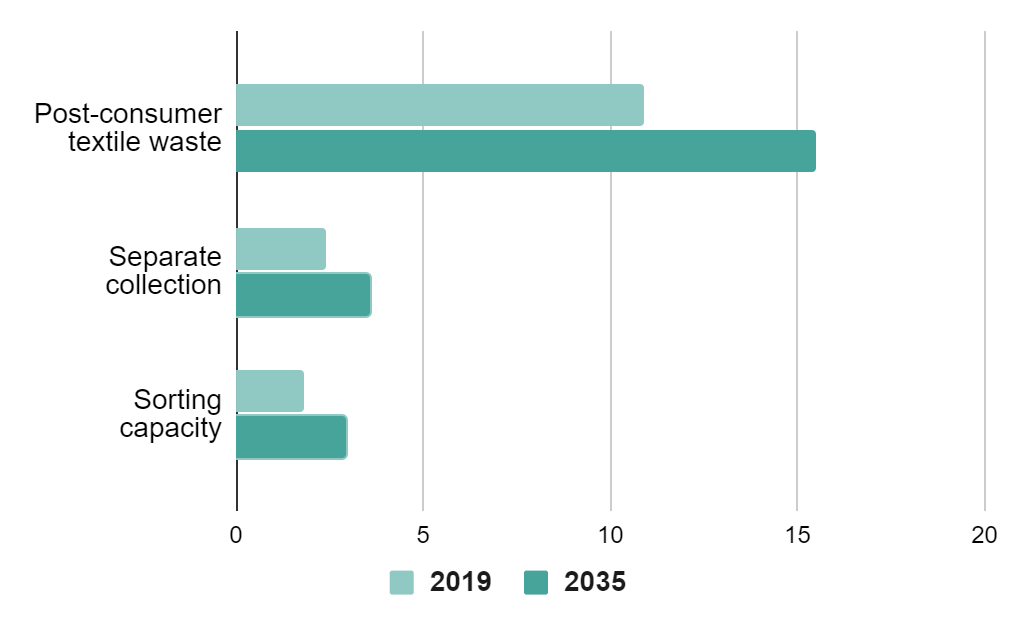

Simply increasing the capacity to collect and sort textile waste is a futile task, as long as the overall volumes of production and consumption keep on growing, as a projection by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre for the year 2035 shows:

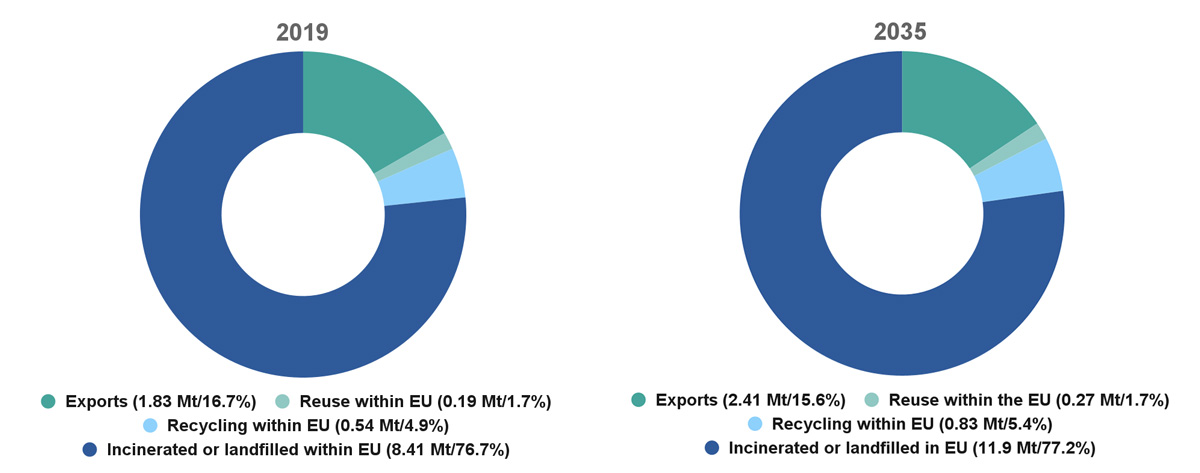

Exports mark a significant portion of the end-of-life-destinations presented here. As the EU market for second-hand textiles is saturated, the collection is moststly shipped abroad—out of sight, out of mind. Donations can even act as a guilt-free output system from consumers’ wardrobes, making space for the next fashion haul.

Despite this bleak outlook, we mustn’t be disheartened to place additional efforts on improving repair and reuse systems, and here is how.

Optimised collection and sorting systems play a pivotal role as enablers of circularity. Funding for those systems will come from Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes in a few years time across the EU, while in France and the Netherlands those schemes have already been introduced.

To become real drivers for circularity, those systems need to go beyond solely distributing funds to waste management and hold producers accountable for the products they release onto the market.

An important tool to enhance reuse and repair in the French system is the allocation of a percentage of the fees collected to a fund dedicated to financing the transition to circularity: the French Solidarity Reuse Fund.

EPR can also address fast fashion directly by first requiring producers to disclose production volumes so that policymakers can focus on fashion's biggest polluters. Second, EPR could be utilised as a form of tax on the number of items placed on the market. For example, EPR fees could increase as soon as a certain volume threshold is reached. Brands would receive a bonus for a lower amount of products placed on the market, which would reward business models embracing circular activities such as leasing, repairing, and reusing clothes. The cost of placing an item on the market would increase as more new items are placed on the market. In France, new eco-modulation criteria have been adopted based on marketing and industrial practices; this could include a levy on volumes.

Setting national to regional targets for collection and reuse can further push producers to act. EPR for textiles in the Netherlands introduced targets (including on collection, reuse, recycling, and fibre-to-fibre recycling), but also the long-standing French EPR scheme includes targets. While issues remain with the governance of Producer Responsibility Organisations (PROs), and the limited leeway in EPR fee modulation has hampered product design changes, EPR still represents the most important financial mechanism to support the reuse economy.

Another option to financially support the reuse economy are direct subsidies, as introduced by the Flemish regional government to support social enterprises. This financial support did not only increase the employment opportunities for vulnerable groups; it has also made Flanders a leader in circularity.

Kringwinkel in Flanders is a non-profit organisation, with the mission to create job opportunities for disadvantaged groups, and the social enterprise currently employs more than 6000 people. The Flemish government’s scheme to support social enterprises covers 48% of the resources Kingwinkel requires to maintain its operation, primarily in the form of wage support, while 52% of the resources come from profits from sales. In Flanders, supporting social economy actors leads to long-term savings on social benefits for the government. For Kringwinkel, the sale of reused textiles generates the largest share of revenue among all second-hand goods sold.

Flanders’ institutional framework recognises one reuse centre per region by the waste agency to avoid competition, and every local authority must have a formal cooperation agreement with at least one reuse centre. Flanders also has a reuse target of 8 kg/capita that must be realised through reuse centres.

One challenge of the system is that there is too much reusable women’s clothing that does not actually sell. A potential future challenge may arise when the EPR for textiles is introduced, which could sideline the social reuse sector in favour of recycling in case it can provide higher value generation.

To boost local repair, several Austrian federal states have implemented a ‘repair bonus’ that reimburses citizens up to 50% of the total cost of a repair. Education and skills training are equally important when boosting the sector. Traditional skills like repairing, mending, and sewing clothes are less common now than several decades ago. Including those skills in school curricula and offering training opportunities for professionals can bring back this essential knowledge.

Moreover, increasing the demand for second-hand textiles could be generated through certain public procurement actions and guidelines introduced by the city. For example, requirements could be added mandating that workwear in the public sector must be second-hand.

Supporting product-as-a-service business models such as ‘Clothing Libraries’ is another way of keeping clothes in the loop for longer while allowing consumers to enjoy novelty in their wardrobe. Det Kollektive Klædeskab (the collective wardrobe) in Copenhagen, Denmark, is a sharing initiative where members can hand in clothes that they no longer use and gain points that can be used to purchase second-hand clothes in the stores. The initiative allows for clothing to be circulated between many users, thereby prolonging their usage, and gives their customers an alternative to shopping for new clothing.

Finally, support for non-market exchange consumption models, including citizen-led repair cafes, clothing swaps, or reuse events, can meaningfully promote lifestyles more based on sufficiency and less on consumption. Cities can be key actors here, providing the necessary space for such events and businesses, or at least subsidising some of the costs required. They can also receive extra promotion and attention within public communications, helping to direct citizens to these events and spaces. Cities can also offer discounts to businesses or subsidised/free tickets to events, which promote and support business and consumption models that look more at sufficiency and slow fashion.